Acne Bacteria May Turn a Clogged Pore into an Inflamed Pimple

The Essential Info

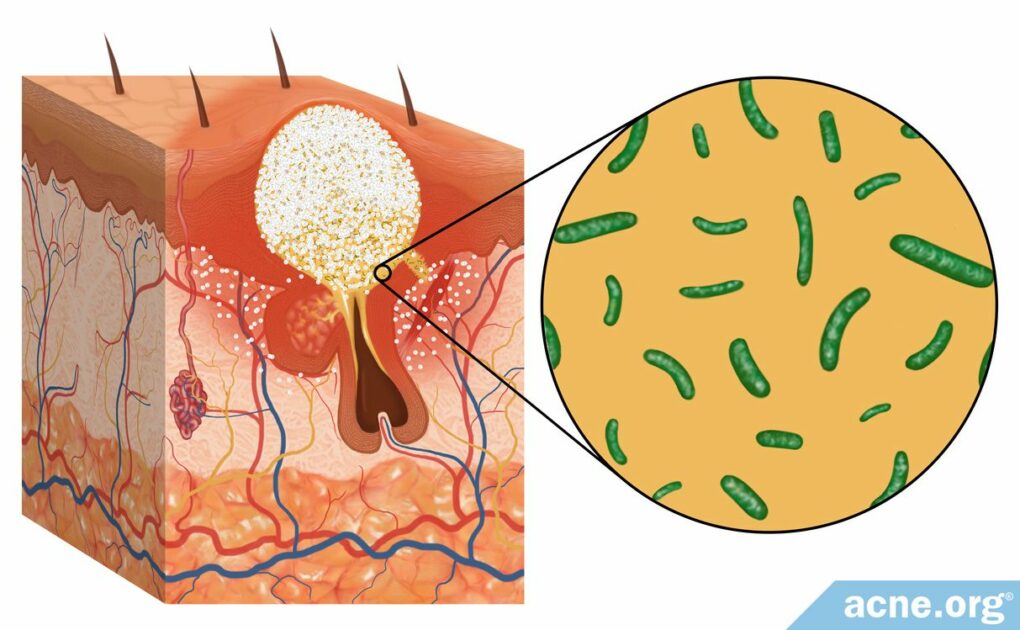

Acne forms when a skin pore becomes clogged and skin oil that normally drains to the surface gets trapped inside.

Living inside this skin oil is a type of acne bacteria called Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes). When skin oil gets trapped, C. acnes multiplies. Research shows us that this type of bacteria then increases inflammation in the pore, leading to the redness and soreness that we see in acne lesions.

This is why medications like benzoyl peroxide that kill acne bacteria work well to combat acne.

However, acne is not first-and-foremost a bacterial disease. As science marches on, researchers are realizing that acne is at its core an inflammatory disease, and bacteria are simply one component in its development.

This article is a deep scientific dive into how bacteria may be involved in acne. If you’re a nerd like me, you may enjoy it. 🙂

The Science

- Steps in Acne Development

- The Role of Bacteria in Acne

- Six Subtypes of Acne Bacteria

- Potential New Therapeutic Options

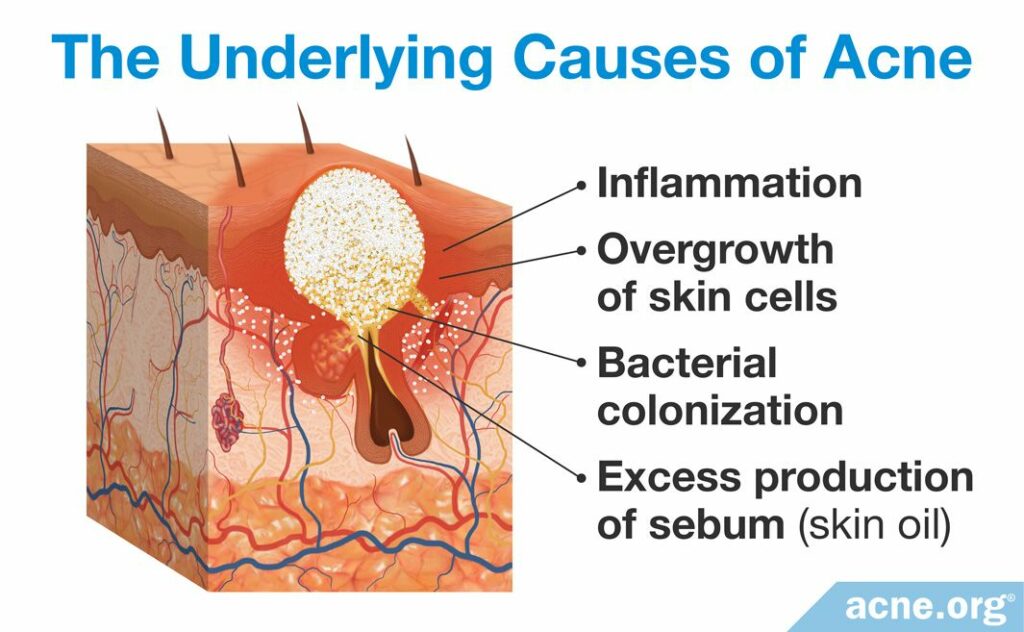

Acne is a complex disease with many contributing factors, and the scientific community still does not understand its underlying causes. Researchers believe that a sequence of steps, including inflammation, excess production of skin oil (sebum), overgrowth of skin cells, and bacterial colonization all play a role in acne development. However, the order in which these steps occur, and the relationship between them, still is unclear and is a subject of scientific debate.

In this article we will start by looking at the steps in acne development and then look more closely at the role of bacteria specifically.

Steps in Acne Development

For years, scientists have used a classic model that explains the steps that lead to acne in the following order:

- An overgrowth of skin cells and overproduction of skin oil (sebum) leads to the formation of a clogged pore

- The clogged pore becomes colonized with acne bacteria (C. acnes)

- Inflammation ensues

However, recent evidence indicates that this classic model that scientists have used for years may be incorrect and that inflammation may actually be the first step in acne development, and this inflammation leads to the initial clogged pore.1-3 Colonization of bacteria still comes later in the process, but instead of causing inflammation, it simply worsens already existing inflammation. In other words, acne is now viewed as a primarily inflammatory disease that becomes worse due to the presence of bacteria.4,5

The Role of Bacteria in Acne

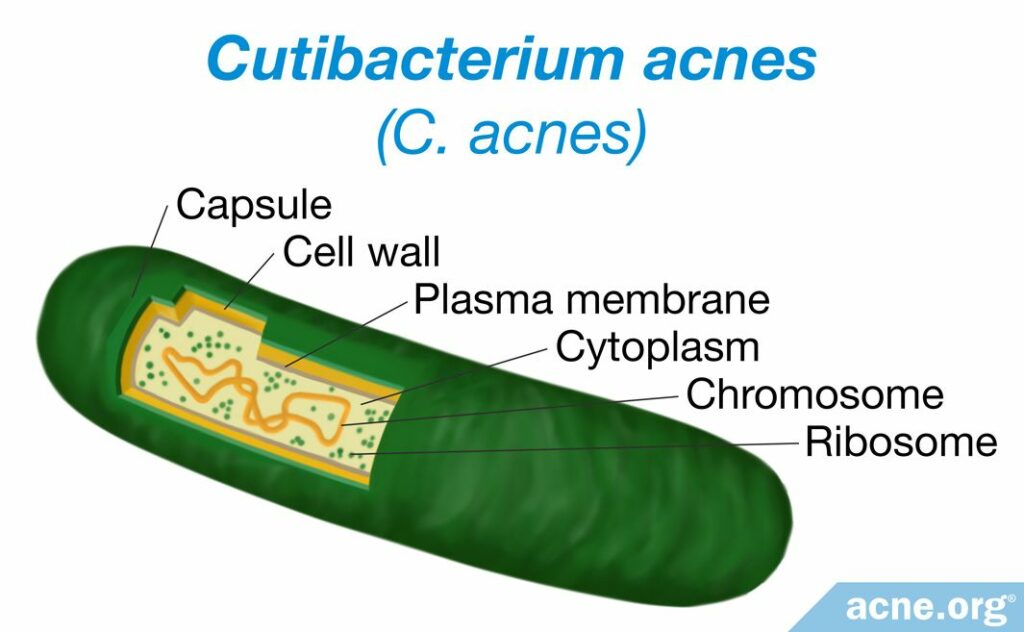

A variety of different microorganisms, including the “acne bacteria” called Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes) live on the skin of almost all adults.4 C. acnes is a type of anaerobic bacteria, which means it cannot survive long in the presence of oxygen. It lives mostly in the oily parts of the body where acne develops, such as the pores of the face and of the upper trunk (chest/back). According to a 2009 article in the journal Science:

“[T]he [skin oil] glands of the face, scalp, chest and back produce large amounts of […] sebum and are the sites where […] Cutibacterium acnes predominates.”6

The fact that C. acnes lives on normal skin and yet not all people develop acne indicates that its mere presence is not sufficient to cause acne. At the same time, C. acnes does indeed appear to contribute to acne, and scientists are still trying to determine exactly what role it plays and under what circumstances it transforms from a normal skin-microbe into one that contributes to disease.

To answer this perplexing question, scientists have studied acne lesions to determine whether C. acnes and/or other microorganisms must be present in a skin pore for an acne lesion to form. Investigations of inflamed acne lesions indicate a surprising finding: C. acnes and another strain of bacteria called S. epidermis are often, but not always, present in acne lesions. These results indicate that C. acnes and other microorganisms do not always appear in acne lesions, which means that the presence of these microorganisms is not always required in order for inflamed, red, and sore acne to occur.4

Six Subtypes of Acne Bacteria

To make matters even more complicated, it turns out that there are six different subtypes of the acne bacteria C. acnes:7

- Type IA1

- Type IA2

- Type IB

- Type IC

- Type II

- Type III

While most people have acne bacteria on their skin, new research suggests that people who are prone to acne may have a higher amount of specific subtypes of these bacteria. For example, people with acne may have more Type IA1 bacteria on their skin compared to people without acne. This subtype may be especially likely to contribute to acne for two reasons:

- Type IA1 bacteria may trigger inflammation more strongly than other subtypes of C. acnes.

- Type IA1 bacteria may be better at forming biofilms. A biofilm is a large cluster of bacteria held together in a “sheet” of sugar molecules produced by the bacteria themselves. Scientists speculate that biofilms may get stuck in pores and contribute to pore clogging.7,8

Even though bacteria are not always found in acne lesions, they usually are, and the presence of bacteria can make inflammation worse. In essence, bacteria probably intensify any redness and soreness that may already be brewing in acne lesions. Let’s look a bit more deeply into how this occurs.

How C. acnes Contributes to Inflammation of Acne

While the exact role of C. acnes or other bacteria in acne development remains unknown, and the presence of bacteria is not always necessary for acne lesions to occur, scientists do know that C. acnes bacteria contain genes that can activate the immune system and cause the immune system to then create inflammation.9 To put it simply, the immune system recognizes C. acnes bacteria as “invaders” and sends in troops of inflammatory molecules to attack these “invaders.”

Expand the section below if you are curious to delve a bit deeper into how C. acnes can sometimes make inflammation worse.

Expand to read details of research

In addition to activating the immune system, studies show that C. acnes can also activate groups of proteins called inflammasome complexes in the skin, which stimulate the release of inflammatory molecules called cytokines.11,12 Previous research has linked activation of these inflammasome complexes to other inflammatory skin conditions, such as psoriasis.

A 2014 study in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology found that C. acnes interacted with a type of white blood-cell in the skin called a monocyte cell and “trigger[ed] a key inflammatory mediator, […], suggesting a role for inflammasome-mediated inflammation in acne pathogenesis.”11

Another 2014 study in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology found that C. acnes also appeared to trigger an additional inflammatory immune response in cells called Th17 cells, which release inflammatory cytokines and create localized chronic inflammation. Previous research has shown that Th17 immune responses are associated with autoimmune inflammatory disorders, such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and multiple sclerosis.12

According to a review article published in F1000 Research in 2018, C. acnes bacteria produce two additional types of proteins that can contribute to inflammation:

1. CAMP factor proteins: These proteins can kill cells in skin pores, triggering inflammation.

2. Porphyrins: These proteins create free radicals, which are harmful substances that can cause skin damage and trigger inflammation.7

As we can see from these studies, C. acnes appears to stimulate several different inflammatory mechanisms, including activating the immune system and creating inflammation directly in the skin, all of which ultimately contribute to the inflammatory redness and soreness of acne.

Potential New Therapeutic Options

While antibiotics are one option for reducing the number of potentially harmful bacteria like C. acnes, the medical community is starting to recognize that prescribing antibiotics long-term is a bad idea. This is because long-term antibiotics use contributes to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. For instance, a recent study suggest that C. acnes bacteria have developed resistance to macrolides (the most commonly prescribed antibiotics for acne treatment) in over half of patients with acne.13 Today, guidelines for doctors recommend prescribing other treatments for acne and either avoiding antibiotics altogether, or only prescribing them for short periods of up to 3 months.7

Luckily, as scientists gain a greater understanding of the role of bacteria, particularly C. acnes, in the processes underlying acne, new treatment options become possible, including medications that target particular parts of the immune system that are susceptible to activation by bacteria, and new vaccines that target C. acnes, to name just a few.9,12,14

References

- Jeremy, A. H., Holland, D. B., Roberts, S. G., Thomson, K. F. & Cunliffe, W. J. Inflammatory events are involved in acne lesion initiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 121, 20 – 27 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12839559

- Do, T. T. et al. Computer-assisted alignment and tracking of acne lesions indicate that most inflammatory lesions arise from comedones and de novo. J Am. Acad. Dermatol. 58, 603 – 608 (2008). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18249468

- Metiko, B., Brooks, K., Burkhart, C. G., Burkhart, C. N. & Morrell, D. Is the current model for acne pathogenesis backwards? J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 72, e167 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25981026

- Shaheen, B. & Gonzalez, M. A microbial aetiology of acne: what is the evidence? Br. J. Dermatol. 165, 474 – 485 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21495996

- Suh, D. H. & Kwon, H. H. What’s new in the physiopathology of acne? Br. J. Dermatol. 172 Suppl 1, 13 – 19 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25645151

- Grice, E. A. et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science 324, 1190 – 1192 (2009). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2805064/

- Platsidaki, E. & Dessinioti, C. Recent advances in understanding Propionibacterium acnes (Cutibacterium acnes) in acne. F1000 Res. 7, F1000 (2018). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6305227/

- McLaughlin, J., Watterson, S., Layton, A. M., Bjourson, A. J., Barnard, E. & McDowell, A. Propionibacterium acnes and acne vulgaris: New insights from the integration of population genetic, multi-omic, biochemical and host-microbe studies. Microorganisms 7, 128 (2019). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6560440/

- Beylot, C. et al. Propionibacterium acnes: an update on its role in the pathogenesis of acne. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 28, 271 – 278 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23905540

- Contassot, E. & French, L. E. New insights into acne pathogenesis: propionibacterium acnes activates the inflammasome. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134, 310 – 313 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24424454

- Qin, M. et al. Propionibacterium acnes Induces IL-1beta secretion via the NLRP3 inflammasome in human monocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134, 381 – 388 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23884315

- Agak, G. W. et al. Propionibacterium acnes Induces an IL-17 Response in Acne Vulgaris that Is Regulated by Vitamin A and Vitamin D. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134, 366 – 373 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23924903

- Zhang, J., Yu, F., Fu, K., Ma, X., Han, Y., Ali, C. C., Zhou, H., Xu, Y., Zhang, T., Kang, S., Xu, Y., Li, Z., Shi, J., Gao, S., Chen, Y., Chen, L., Zhang, J. & Zhu, F. C. acnes qPCR-based antibiotics resistance assay (ACQUIRE) reveals widespread macrolide resistance in acne patients and can eliminate macrolide misuse in acne treatment. Front. Public Health 10, 787299 (2022). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35372231/

- Qin, M. et al. Nitric Oxide-Releasing Nanoparticles Prevent Propionibacterium acnes-Induced Inflammation by Both Clearing the Organism and Inhibiting Microbial Stimulation of the Innate Immune Response. J. Invest. Dermatol. 135, 2723 – 2731 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26172313

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products