A Blackhead Is a Small, Dark-colored Clogged Pore

The Essential Info

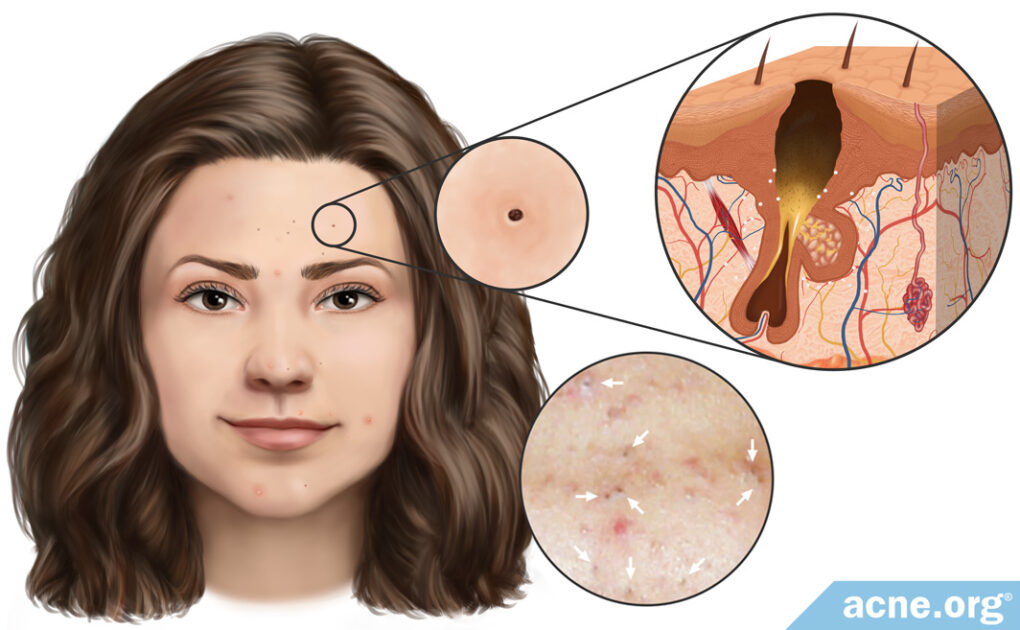

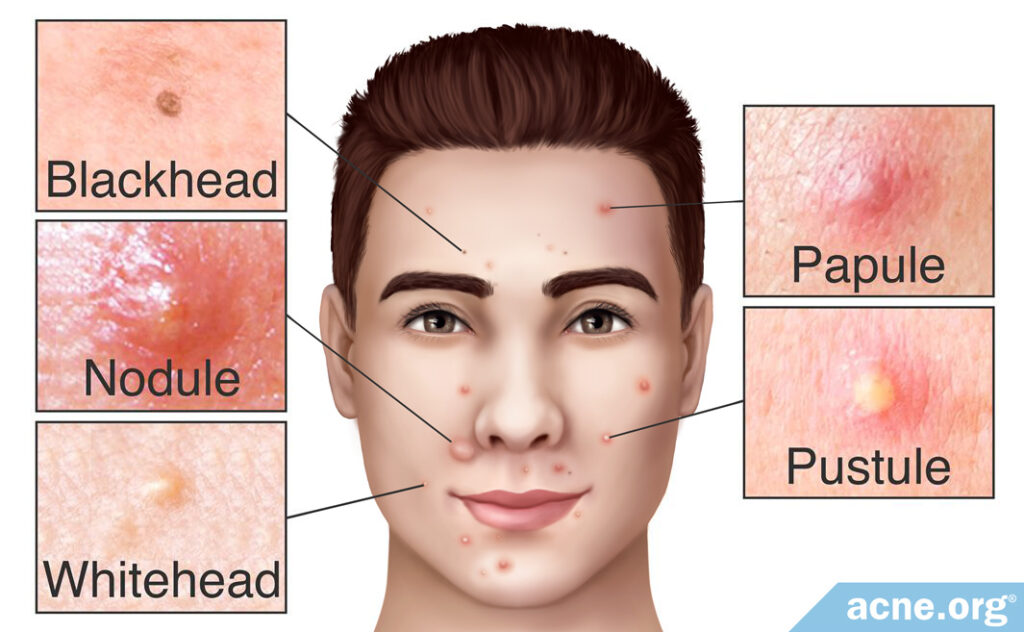

Blackheads, also called open comedones, are small, non-inflammatory, black- or brown-colored clogged pores that most often appear on the face.

They develop when a pore becomes partially clogged and begins to fill up with skin oil. Because the pore is only partially blocked, oxygen from the air seeps in and reacts with melanin in the clogged pore, and this is what causes the black or brown color we see with blackheads.

Blackheads are stubborn lesions that normally last between 45-60 days. They either go away on their own, or develop into an inflammatory lesion, such as a papule, pustule, nodule, or cyst.

My Advice: The best way to handle blackheads is to prevent them in the first place with a proper regimen. Once you have them, they are hard to get rid of, and any manual method you use to get rid of them, like Biore® strips or manual comedone extraction at an esthetician’s office, will have the following 2 downsides:

- They cause tons of physical irritation, and physical irritation can easily lead to more acne and keep you in a vicious cycle.

- The blackhead will more than likely fill back up in the weeks after extraction, so there’s not much point in manually extracting them anyway.

The Science

- How Blackheads Develop

- Dilated Pore of Winer: A Special Type of Blackhead-like Lesion

- How Long Do Blackheads Remain on the Skin?

- What Causes Blackheads?

- Conclusion

Blackheads, also called open comedones, are brown- or black-colored clogged pores (comedones) that mainly form on the face, but can also be found on the neck, back, chest, shoulders, and upper arms. Dermatologists classify blackheads as “non-inflammatory” acne lesions because they are not red, swollen, or painful.

Blackheads form when microscopic hair follicles, often called pores, become partially clogged by skin cells and skin oil (sebum). Once a blackhead develops, it can remain on the skin for several weeks or even months, after which it either resolves on its own or develops into a red, swollen, sore “inflammatory” acne lesion.

Most people develop blackheads during their teenage or young adult years, but developing them at an older or younger age is also common.1,2

How Blackheads Develop

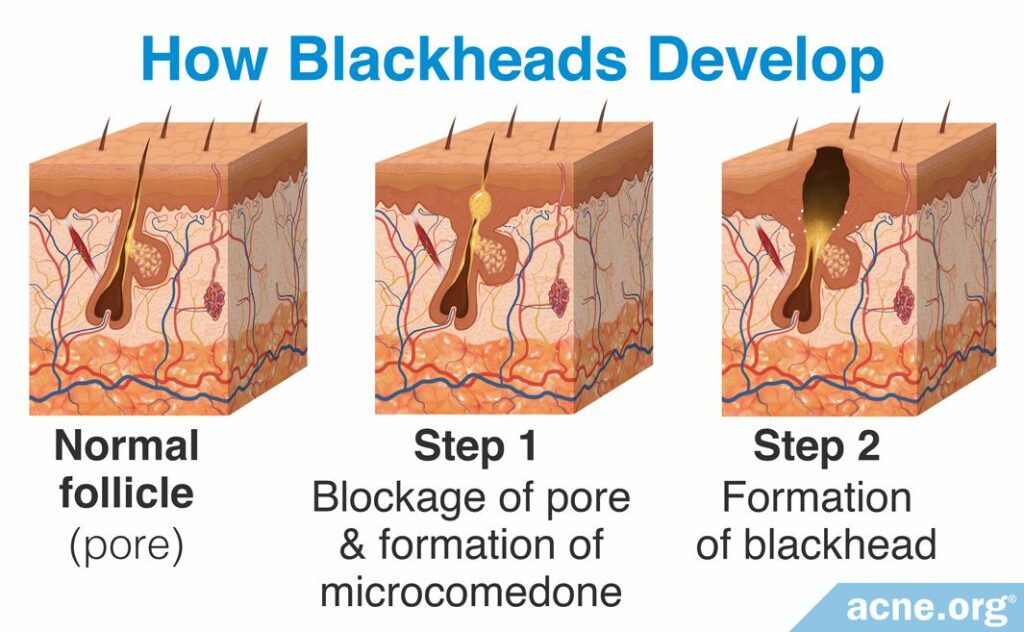

Blackheads develop in two steps:

Step 1 – Blockage of pore & formation of a microcomedone

All acne lesions begin with microscopic hair follicles in the skin, called pores.

Attached to these pores are skin oil (sebum) glands. Normally, sebum moves up the pore and is expelled onto the surface of the skin. However, in acne, the opening to the pore becomes clogged. When the pore first becomes clogged, it is not visible to the naked eye and is called a microcomedone.

Step 2 – Formation of blackhead (comedone)

After a microcomedone forms, the sebum, which is unable to escape the pore, begins to accumulate.

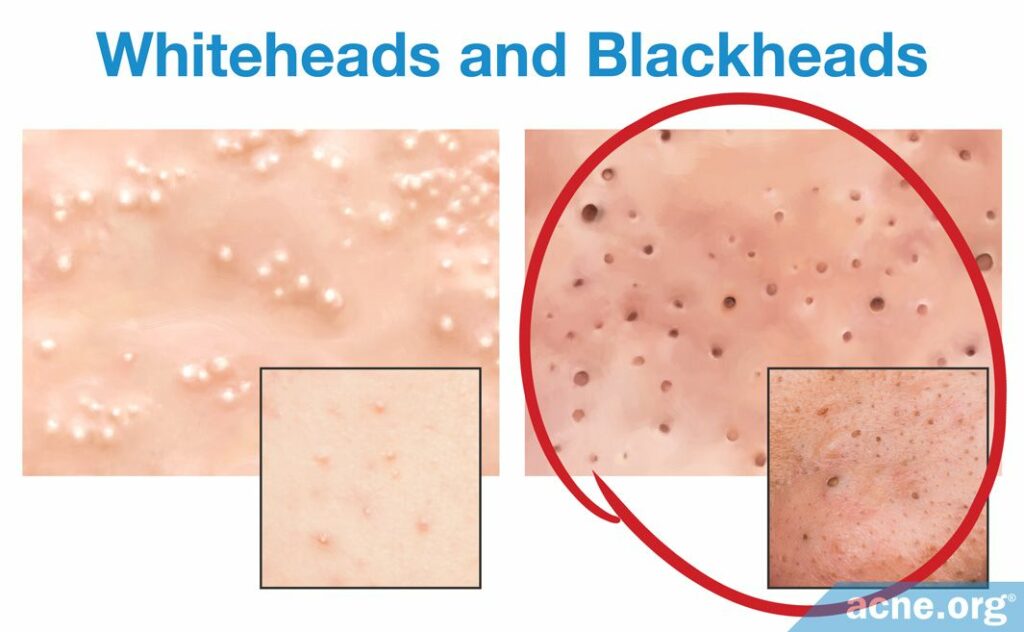

As more sebum builds up, the microcomedone grows larger and becomes a visible comedone. There are two types of comedones, blackheads and whiteheads:

- Blackheads are called open comedones, because the opening of the pore is only partially blocked. This means that sebum can still escape the pore to some degree, and that oxygen, from the air, can enter into the pore. The air that enters the pore interacts with the sebum inside the pore, causing a chemical reaction called oxidation, which is responsible for the characteristic black or brown hue of a blackhead. Once developed, a blackhead can remain on the skin for several weeks or longer.3

- Whiteheads are called closed comedones, because the opening of the pore is completely blocked, and nothing can enter or leave the pore. When the sebum cannot escape the pore, it accumulates, and this buildup of sebum gives the whitehead its characteristic white or skin-colored hue. Once developed, a whitehead remains on the skin for several days.3

Dilated Pore of Winer: A Special Type of Blackhead-like Lesion

Occasionally, some people develop a lesion that looks like a gigantic blackhead that may be up to 1 cm wide, usually on the face, chest, or upper back. This is called a dilated pore of Winer and is actually a separate phenomenon. Although anybody can develop a dilated pore of Winer, they are most common in men aged 40 or older with a previous history of severe acne.4

If you notice this type of lesion on your skin, see a dermatologist to have it removed. Do not try to squeeze or remove the lesion yourself, as this may trigger swelling, pain, and a potential infection.

How Long Do Blackheads Remain on the Skin?

A 1974 study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology found that blackheads, on average, remain on the skin between 45 and 60 days, but can last up to at least 98 days. After this time, a blackhead will either resolve on its own or develop into an inflammatory acne lesion.5

What Causes Blackheads?

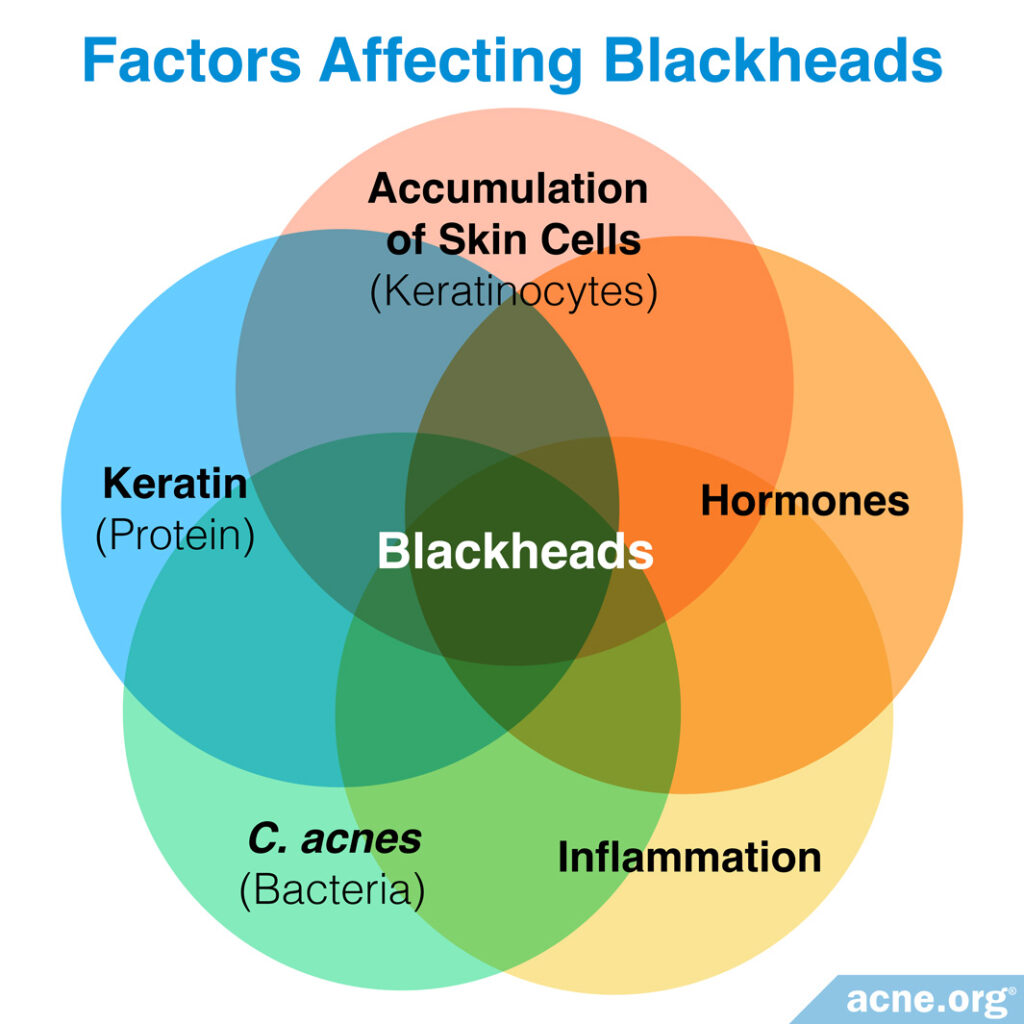

Scientists believe that several factors contribute to the development of a blackhead.6-11

- Inflammation: Inflammatory molecules have been found in blackheads, although they are classified as “non-inflammatory” acne lesions. One study found that the inflammatory molecule interleukin 1 (IL-1) is found in up to 76% of comedones, including both blackheads and whiteheads. This suggests that although blackheads are not red, sore, or swollen, there is almost always inflammation present in them and that it likely plays a role in their development.

- Hormones: Increased hormones, especially androgens, play a major role in the development of acne. In fact, without hormones, acne will not develop. So increased levels of androgens, which can be found in both males and females, can result in more blackheads.

- Accumulation of skin cells: Skin cells known as keratinocytes are constantly produced and shed from the skin. In acne, an accumulation of both new skin cells and dead skin cells occurs along the wall of the pore, leading to the development of blackheads and whiteheads.

- Keratin: Keratin is an especially sticky protein normally produced by keratinocytes. As there is an accumulation of these cells in the pore, there is also an accumulation of keratin. The keratin causes the skin cells to stick together, facilitating the development of a comedone.12-14

- Acne bacteria (C. acnes): A type of bacteria called C. acnes, which lives on the skin of most people and eats skin oil, may also contribute to blackhead formation. When this type of bacteria overgrows on the skin, it can form a layer called a biofilm that makes dead skin cells more likely to stick around and clog pores.15

Conclusion

Blackheads, also known as open comedones, are small, non-inflammatory, black- or brown-colored comedones that most often develop on the face. They develop when a pore becomes clogged by skin cells and begins to fill up with sebum. Blackheads remain on the skin for several weeks or months before either resolving on their own, or developing into an inflammatory lesion, such as a papule, pustule, nodule, or cyst.

References

- Oberemok, S. & Shalita, A. Acne vulgaris, I: Pathogenesis and diagnosis. Cutis 70, 101 – 105 (2002). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12234155

- Pareek, V., Khunger, N., Sharma, S. & Dhawan, I. An observational study of clinical, metabolic and hormonal profile of pediatric acne. Indian J Dermatol 67, 645-650 (2022). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36998833/

- Brogden, R. & Goa, K. Adapalene. Drugs 53, 511 – 519 (1997). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9074847

- Benedetto, C. J. & Athalye, L. Dilated pore of Winer (black head) [Updated 2019 Dec 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532967/

- Gollnick, H. Current concepts of the pathogenesis of acne. Drugs 63, 1579 – 1596 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12887264

- Rao, J. Acne Vulgaris: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology. Emedicine.medscape.com (2016). At https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1069804-overview#a2

- Dreno, B. & Poll, F. Epidemiology of acne. Dermatology 206, 7 – 10 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12566799

- Pochi, E. The pathogenesis and treatment of acne. Annu Rev Med 41, 187 – 198 (1990). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5986265/

- Kligman, A. Postadolescent acne in women. Cutis 48, 75 – 77 (1991). https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/354887

- Orentreich, N. & Durr, N. The natural evolution of comedones into inflammatory papules and pustules. J Investig Dermatol 62, 316 – 320 (1974). https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/82174419.pdf

- Do, T. et al. Computer-assisted alignment and tracking of acne lesions indicate that most inflammatory lesions arise from comedones and de novo. J Am Acad Dermatol 58, 603 – 608 (2008). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18249468

- Danby, F. Ductal hypoxia in acne: Is it the missing link between comedogenesis and inflammation? J Am Acad Dermatol 70, 948 – 949 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24742839

- Tanghetti, E. The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 6, 27 – 35 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3780801/

- van Steensel, M. A. M. & Goh, B. C. Cutibacterium acnes: Much ado about maybe nothing much. Exp Dermatol 30, 1471-1476 (2021). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34009698/

- Xu, H. & Li, H. Acne, the skin microbiome, and antibiotic treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol 20, 335-344 (2019). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30632097/