Increases in the Amount of Skin Cells and Skin Proteins May Lead to Clogged Pores

The Essential Info

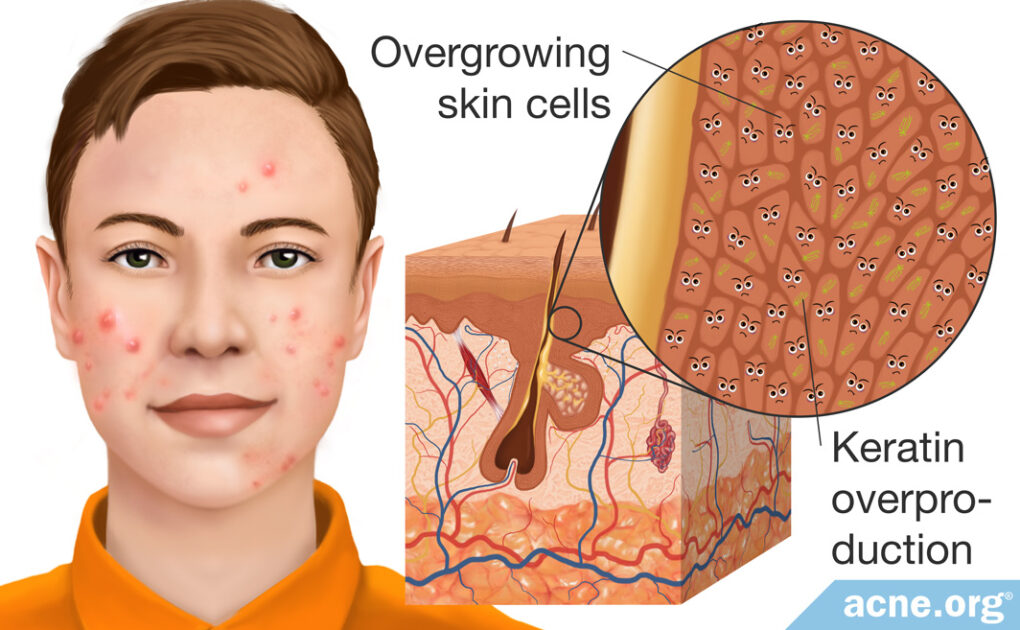

Hyperkeratinization is the word dermatologists and biology researchers use to refer to the overgrowth of skin cells, called keratinocytes, and a corresponding overproduction of a protein that keratinocytes produce, called keratin.

The overgrowth of keratinocytes and keratin causes the walls of a skin pore to stick together, leading to a clogged pore. Within this clogged pore, skin oil that normally drains to the surface is trapped, bacteria grows, and an acne lesion is born.

In other words, hyperkeratinization is an initial step in the formation of an acne lesion.

This article will take a deep dive into the biology of hyperkeratinization. Woohoo!

The Science

- What Triggers Hyperkeratinization?

- Hyperkeratinization and the Formation of Acne

- Some Topical Acne Treatments Fight Hyperkeratinization

Caution: Deep science ahead! This is interesting biology, but you’ll want to make sure you put your thinking cap on for this one. 🙂

Hyperkeratinization is a term used to refer to the excessive growth of skin cells, called keratinocytes, as well as a skin protein, called keratin. Why is this an often-used word in acne? Because hyperkeratinization contributes to the formation of clogged pores, called comedones, during the early stages of acne formation. Acne cannot form without a pore first becoming clogged, so let’s have a close look at how skin cells over-grow, stick together, and form clogs in skin pores.

First, we’ll look more closely at keratinocytes and keratin.

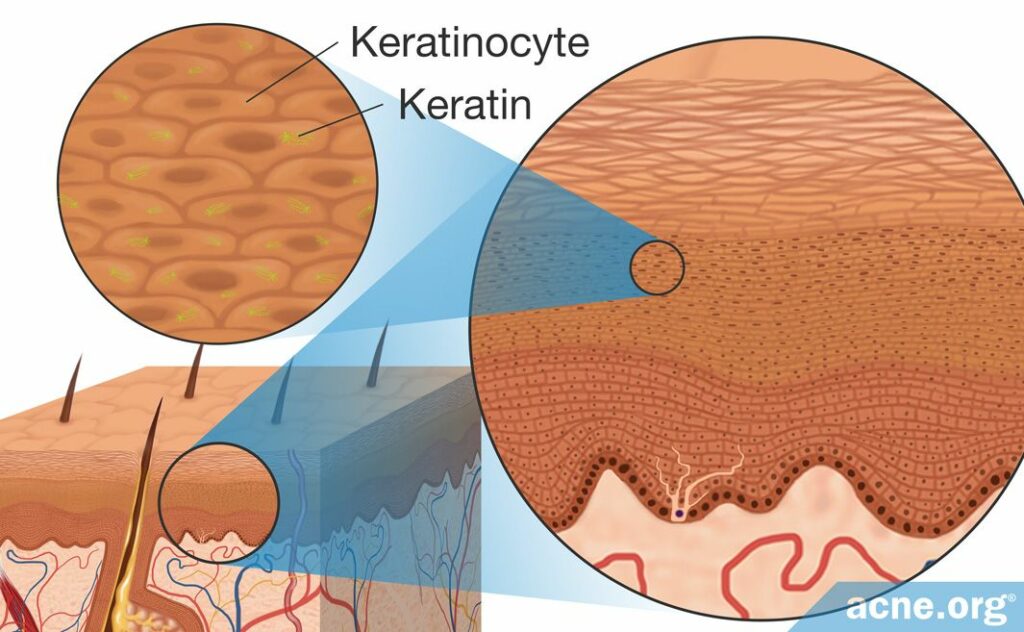

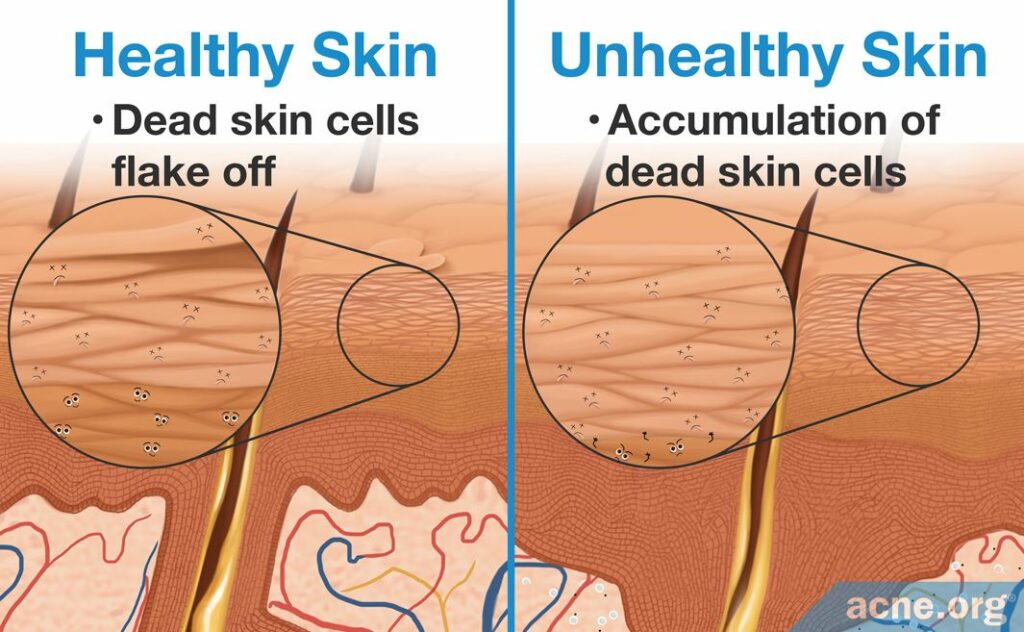

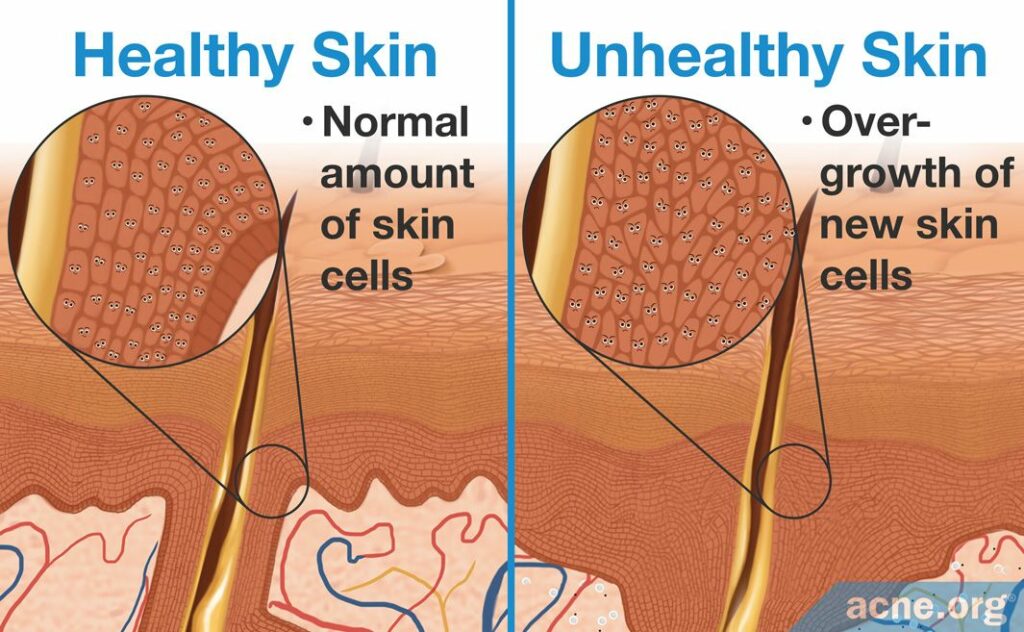

- Keratinocytes are the main skin cells found in the epidermis (top layer of the skin). In healthy skin, there is a constant renewal of skin cells, with new cells replacing old ones that have flaked off the skin. During hyperkeratinization, the old skin cells do not flake off the skin, and instead accumulate on the skin’s surface.

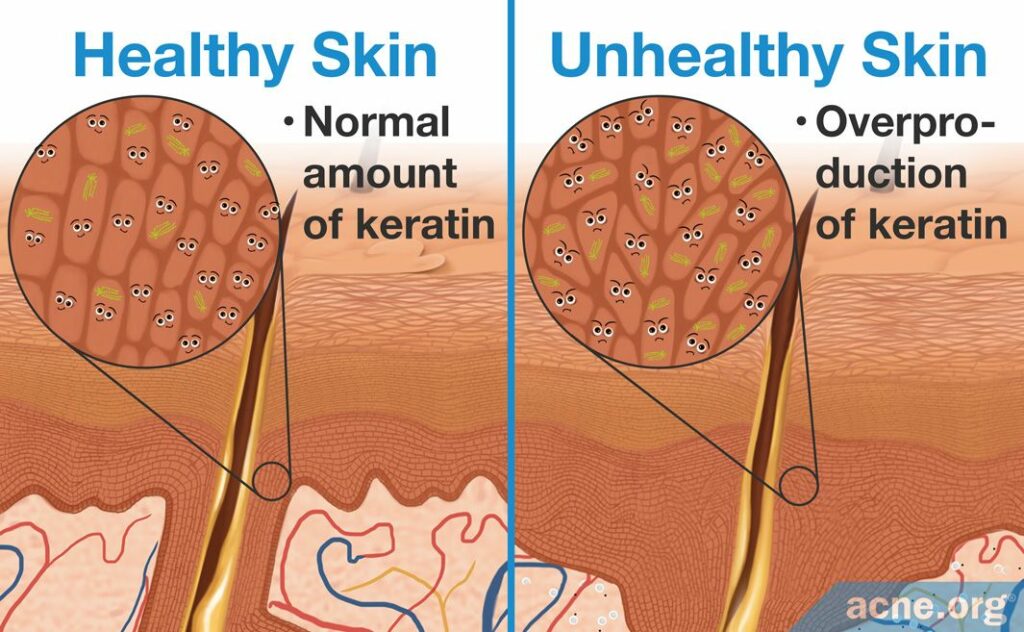

- Keratin is an important protein produced by keratinocytes. It is found in the skin, hair, and nails and works by acting like glue to hold cells together. This provides strength to these tissues. The more keratin in a tissue, the denser and stronger that tissue will be because the sticky keratin holds everything together. During hyperkeratinization, keratinocytes begin to accumulate in the epidermis, and the increase in the number of keratinocytes also increases the amount of keratin.

What Triggers Hyperkeratinization?

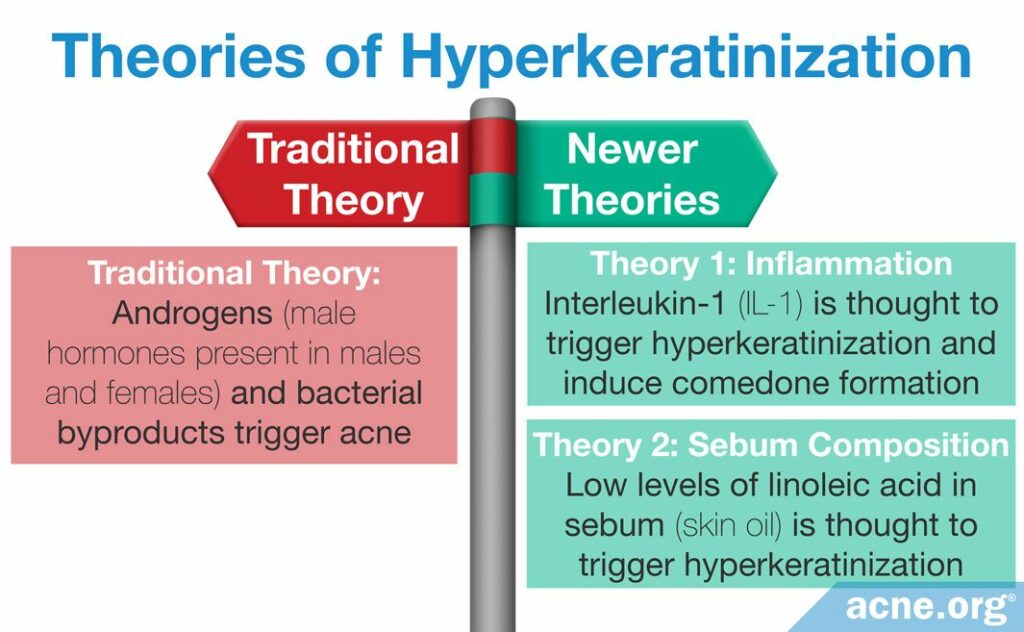

There are three theories on how acne is formed, all of which involve hyperkeratinization.

- Traditional Theory: The traditional theory contends that there are two triggers of hyperkeratinization. The first is androgens, which are male hormones found in both males and females, and the second is bacterial growth in the skin. In acne, this theory posits, high levels of androgens, or increased sensitivity to androgens, causes the skin to produce too much skin oil, called sebum, and inside this sebum, bacteria grow. The byproducts of this bacterial growth, and the androgens themselves, then trigger hyperkeratinization.1-3

- Newer Theory 1 (Inflammation): The first newer theory states that there is one main trigger of hyperkeratinization: inflammation. The specific inflammatory molecule thought to trigger initial hyperkeratinization is interleukin-1 (IL-1). Research has found that IL-1 can induce hyperkeratinization and may “mediate the formation of comedones,” meaning that it may cause clogged pores. Additional research has found that comedones often contain IL-1 levels that are up to a thousand times higher than what is found in unclogged pores. An interesting twist in this theory is that, according to one recent study, it is the presence of acne bacteria that may trigger skin cells to release IL-1, leading to hyperkeratinization and pore clogging. In other words, inflammation that is due, at least in part, to bacteria may jump-start the hyperkeratinization process.4,5

- Newer Theory 2 (Sebum Composition): The second newer theory places the blame on sebum composition. Sebum comprises a variety of different oils, waxes, and fats. One of these fats is linoleic acid. Research has found that in healthy individuals, linoleic acid makes up 45% of sebum, while it makes up only 6% of sebum in individuals with acne. Therefore, linoleic acid may potentially play an important role in the development of acne. Some researchers have suggested that hyperkeratinization may be due to a linoleic acid deficiency.1

Hyperkeratinization and the Formation of Acne

Although researchers are still debating what causes hyperkeratinization, they do know that it contributes to the formation of acne via four events. Let’s have a closer look at how hyperkeratinization occurs, and how it then leads to acne.

1. Accumulation of dead skin cells: In healthy skin, old skin cells die and are replaced by new ones. During hyperkeratinization, the skin cells die but do not flake off the surface of the skin. Instead, they begin to accumulate in the epidermis.6

2. Overgrowth of new skin cells: During hyperkeratinization, new skin cells are produced beneath the accumulated dead ones. These new skin cells are created from cell division, also called cell reproduction. During cell reproduction, a single skin cell divides into two new skin cells. But during hyperkeratinization, this process speeds up, resulting in more cell divisions and the production of too many new skin cells. How do we know this happens? Researchers have studied this faster cell reproduction by looking for increased levels of two proteins called Ki-67 and 3H-thymidine, which are markers for cell reproduction. Inside comedones are high levels of these proteins, meaning that skin cell reproduction occurs rapidly inside comedones. The overgrowth of new skin cells in the epidermis causes the skin to thicken.7,8

3. Overproduction of keratin: The combination of accumulating dead skin cells that contain keratin and an overgrowth of new skin cells that also contain keratin results in a surplus of keratin. Research shows us that keratin is especially increased in the wall lining the pore, causing the walls of the pore to “stick together” and become clogged.6

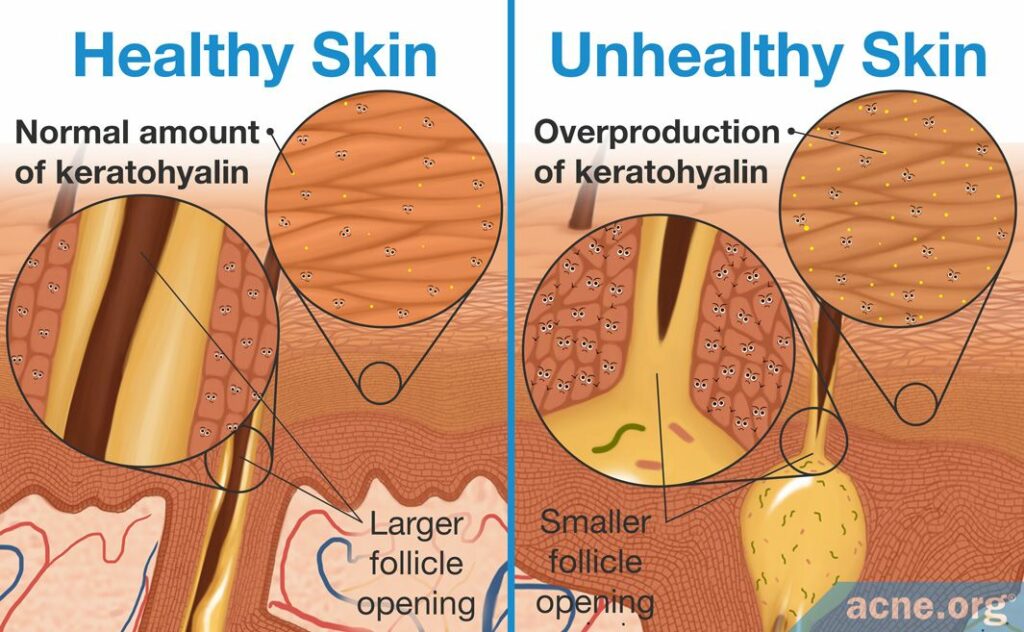

4. Thickening of the skin: The combination of accumulating dead skin cells, an overgrowth of new skin cells, and too much keratin, creates a thickening of the skin, called hyperkeratosis. The epidermis is composed of multiple layers, and the thickening of the skin occurs at both the surface layer and deep layer, through different mechanisms.

- Surface layer: When there is an accumulation of skin cells and keratin in the surface layer, this occurs due to special structures inside the cell membranes called desmosomes and tonofilaments. These structures are what make the keratinocytes stay connected to one another and accumulate. When more skin cells stick together, the surface layer thickens. The thickening of the skin at the surface level can begin to narrow the pores, allowing for sebum to accumulate inside them.1,6,7,9

- Deep layer: Beneath the surface layer of the skin exist other, deeper skin layers. One layer, called the granular layer, can also thicken during hyperkeratinization. This layer thickens when cells called horny cells produce too much of a protein called keratohyalin. This protein acts like keratin, and during hyperkeratinization can thicken the granular layer. Just like in the surface layer, this thickening of the deeper layers can narrow the skin pore.9

In acne-prone skin, hyperkeratinization occurs in areas even without visible acne lesions. Because of this, researchers believe that it may trigger the development of acne lesions in healthy areas.7

Some Topical Acne Treatments Fight Hyperkeratinization

Some topical anti-acne ingredients can work against hyperkeratinization in one of two ways:

- Softening keratin: During hyperkeratinization, overproduction of tough, sticky keratin makes the skin thicker and narrows skin pores. Some topical acne treatments counteract this by softening the tough keratin in the skin.

- Breaking down bonds between keratinocytes: During hyperkeratinization, dead keratinocytes in the outer layer of the skin remain stuck to each other and to the skin surface instead of flaking off in a timely manner. This occurs in part because the desmosomes between the keratinocytes keep them tightly connected. Some topical acne treatments help to loosen the desmosomes, allowing the keratinocytes to shed.10

Topical ingredients that fight hyperkeratinization are known as keratolytics. Common keratolytics that can be useful for improving acne include:10,11

References

- Toyoda, M. & Morohashi, M. Pathogenesis of acne. Med Electron Microsc 34, 29 – 40 (2001). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11479771

- Kurokawa, I. et al. New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol 18, 821 – 832 (2009). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19555434

- Mias, C., Mengeaud, V., Bessou-Touya, S. & Duplan, H. Recent advances in understanding inflammatory acne: Deciphering the relationship between Cutibacterium acnes and Th17 inflammatory pathway. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 37 Suppl 2, 3-11 (2023). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36729400/

- Guy, R., Green, M. & Kealey, T. Modeling Acne in Vitro. J Investig Dermatol 106, 176 – 182 (1996). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8592071

- Selway, J. L., Kurczab, T., Kealey, T. & Langlands, K. Toll-like receptor 2 activation and comedogenesis: implications for the pathogenesis of acne. BMC Dermatol 13, 10-15 (2013). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24011352/

- Degitz, K., Placzek, M., Borelli, C. & Plewig, G. Pathophysiology of acne. JDDG 5, 316 – 323 (2007). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17376098

- Thiboutot, D. The role of follicular hyperkeratinization in acne. J Dermatol Treatment 11, 5 – 8 (2000). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/095466300750163645

- Cunliffe, W. et al. Comedone formation: Etiology, clinical presentation, and treatment. Clin Dermatol 22, 367 – 374 (2004). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15556720

- Hyperkeratosis, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyperkeratosis

- Tolaymat, L. & Zito, P. M. Adapalene. [Updated 2020 Feb 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482509/

- Pennycook, K. B. & McCready, T. A. Keratosis Pilaris. [Updated 2019 Sep 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546708/

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products