Antibiotic Treatment for Acne Is Worsening the Worldwide Problem of Antibiotic Resistance

The Essential Info

Acne is in part a bacterial disease, and antibiotics can help to keep bacteria in check in the short term and to a limited degree in some people. They may also help reduce the inflammatory component of acne, but again, only in the short term and to a limited degree.

However, particularly when taken for extended periods of time, antibiotics can lead to lifelong antibiotic resistance for the user and the world at large.

Because antibiotics produce only limited results, and because their overuse presents such a danger to the patient and larger society, many doctors are now warning that antibiotics should be drugs of last resort, especially in acne treatment, and when they are used, they should be used sparingly and only for short periods of time (maximum 3 months).

Be Your Own Advocate: If your doctor prescribes an oral or topical antibiotic to treat your acne, do not simply accept it without question. Ask your doctor about other treatments you can use instead of antibiotics. If you do use antibiotics, remember that many experts caution against using them for more than 3 months. Also, always take them on time and complete the entire prescribed course, because skipping doses or stopping too soon increases the chances of developing resistant bacteria.

The Science

- What Is Antibiotic Resistance, and Why Is It a Problem?

- Both Topical and Oral Antibiotic Treatment for Acne May Worsen the Problem

- Antibiotics Used to Treat Acne Cause Antibiotic Resistance

- Conclusion

Doctors sometimes prescribe antibiotics to treat acne, especially severe acne. This is highly controversial because they do not tend to work better than other medications, and sometimes do not work at all. They also only offer short-term relief and have significant drawbacks that limit their usefulness.

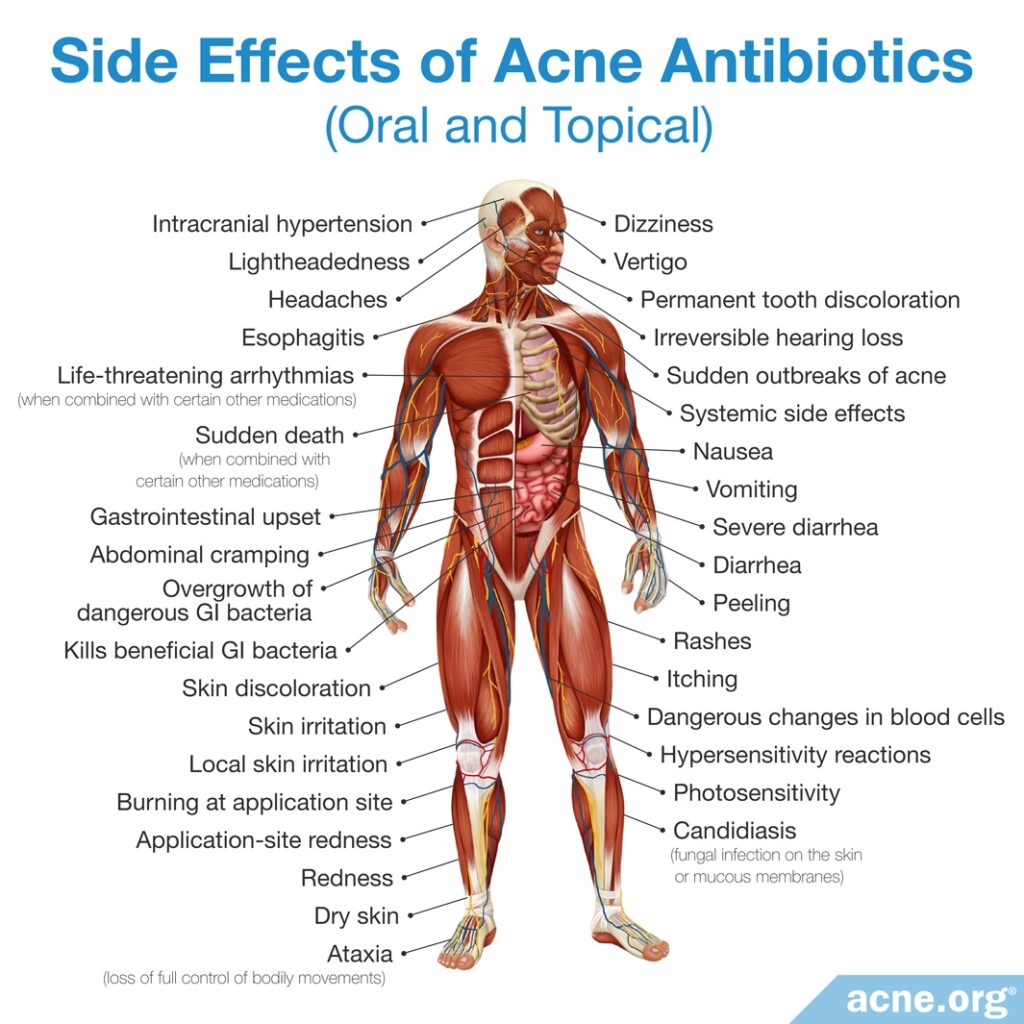

These drawbacks include a wide variety of side effects, which range from mild skin irritation and stomach upset, to permanent tooth and skin discoloration or life-threatening diarrhea.

Another important drawback that is often missed because it does not show up in the short term as an obvious side effect is a phenomenon called antibiotic resistance, which affects not only the individual taking the antibiotic but the world as a whole. In this article, we will discuss the problem of antibiotic resistance.

What Is Antibiotic Resistance, and Why Is It a Problem?

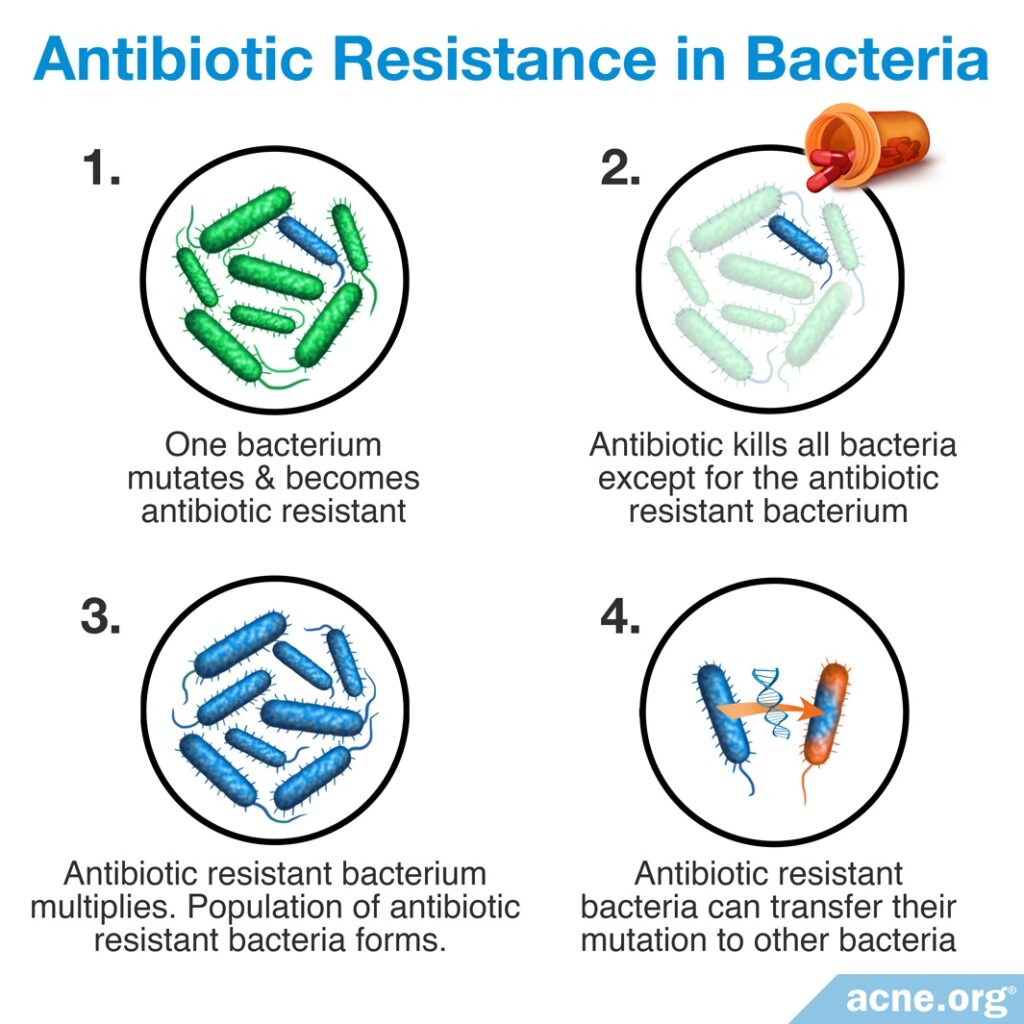

Treatment with antibiotics, especially over long periods of time, leads to antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic resistance means that bacteria become immune to the effects of antibiotics, and eventually the antibiotics can no longer kill the bacteria. Antibiotic resistance is a serious global problem because:

- When bacteria become resistant to an antibiotic, that antibiotic becomes less effective and less able to treat the condition for which it was prescribed, and also any other future bacterial condition that might arise.

- Antibiotic resistance can result in a snowball effect. Bacteria can share their genes with each other and transfer antibiotic resistance from one strain of bacteria to another.

- Antibiotic resistant bacteria can easily be transferred from one person to another simply through touch.

- Ultimately, antibiotic resistance could result in many types of bacteria becoming resistant to all antibiotic medications. This means that doctors may eventually be unable to treat bacterial infections and that people may die from even common bacterial diseases such as strep throat, just like people did before antibiotics were developed.

Both Topical and Oral Antibiotic Treatment for Acne May Worsen the Problem

The world is waking up to how antibiotic prescriptions for acne may increase bacterial resistance, as noted in the quote from a study in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology below:

“Despite the efficacy of antibiotics, there have been calls to limit their use in acne because of concerns for bacterial resistance.”1

In fact, several researchers have pointed out that antibiotic prescriptions for acne are a major source of concern, as acne is the most common condition for which dermatologists prescribe antibiotics. Research suggests that acne patients who are treated with antibiotics not only develop antibiotic-resistant bacteria, but are also very likely to transfer these bacteria to other people.2

Expand to read details of research

For example, according to a 2015 article in Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy, “The worldwide data suggest that the resistance is on the rise and breakpoint levels have been breached in many regions. The transmission of resistant strains to other patients is a major problem. Acne patients are considered to be reservoirs of antibiotic-resistant strains and it was shown…that 41 – 85.7% of untreated close contacts of acne patients who had received antibiotic treatment may carry EM-resistant strains. The resistance seems to move from the acne patients to the community.”2

Because of increasing concern about antibiotic resistance, scientists recommend that antibiotics not be used to treat acne when possible, and when needed, antibiotics should be used only for short periods of time (up to 3 months).1,3

Expand to read scientists’ recommendations

According to the 2007 guidelines in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, “A major problem affecting antibiotic therapy of acne has been bacterial resistance, which has been increasing. For this reason, it is the opinion of the work group that patients with less severe forms of acne should not be treated with oral antibiotics, and where possible the duration of such therapy should be limited.”3

A 2015 article in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology noted that current guidelines recommend limiting antibiotic use to a maximum of three months. The authors stated, “Expert guidelines recommend responsible use of antibiotics in acne in light of emerging resistance. In 2003 and 2009, the Global Alliance to Improve Acne Outcomes published recommendations for acne treatment and suggested limiting the use of systemic antibiotics to 3 months if a patient demonstrates limited clinical improvement. Similarly, European consensus statements published in 2004 and 2012 also explicitly recommended limiting antibiotic use to 3 months.”1

Why Using Antibiotics for Longer Periods of Time Causes Problems

The reason that scientists recommend limiting antibiotic usage to 3 months is that longer treatment periods expose bacteria to the antibiotic for extended periods of time, giving the bacteria time to develop resistance. However, in a worrisome finding, doctors often prescribe antibiotics for considerably longer than 3 months, as 2 recent studies reported.1,4

Expand to read details of studies

A 2014 study in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology found that the average duration of antibiotic therapy is 127 days (approximately 4 months), but that in 18% of cases, the duration exceeds 6 months.4

A 2015 study in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology found that in patients in whom oral antibiotics failed to yield improvement, the average duration of antibiotic therapy before discontinuing treatment and switching to another medication was almost 11 months. The authors noted, “Systemic antibiotics are used widely to treat moderate to severe acne, but increasing antibiotic resistance makes appropriate use a priority…We found that patients [in whom antibiotic treatment had failed] had extended exposure to antibiotics, exceeding recommendations. Early recognition of antibiotic failure…can curtail antibiotic use.”1

Antibiotics Used to Treat Acne Cause Antibiotic Resistance

Studies show that today, 30–50% of the acne bacteria Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes) taken from patients’ skin in most developed countries are resistant to at least some antibiotics.5

Furthermore, recent research indicates that some of the antibiotics that are most frequently prescribed for acne, such as erythromycin and clindamycin, are continuing to create a high incidence of antibiotic resistance. Studies performed in Europe and Hong Kong have found antibiotic-resistant bacteria in approximately half or more of acne patients.6-8 In Jordan and Sweden, the rates of bacteria resistant to erythromycin and clindamycin might even be as high as 60%–70%.9

Expand to read details of studies

For example, as far back as 2002, a study in The British Journal of Dermatology studied 4274 acne patients and found that an average of 51% of patients have harbored colonies of resistant bacteria.6

A 2010 study in the Journal of the German Society of Dermatology found that more than half of acne patients in Europe treated with antibiotics harbored bacteria that were resistant to at least one antibiotic. In addition, this study also found that resistant bacteria could be transmitted between the patient and close contacts, and even between patients and dermatologists. The authors noted, “In Europe, more than half of acne patients harbor erythromycin- or clindamycin-resistant and 20% tetracycline-resistant strains. These strains may be transmitted to close contacts (41 – 86 %) and even physicians (25/39 acne specialists compared to 0/27 physicians without contact to acne patients).”7

A more recent 2013 study in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology collected C. acnes (bacteria associated with acne) samples from acne patients in Hong Kong. This study also found that more than half of the C. acnes samples were resistant to at least one antibiotic. Because of this finding, the authors cautioned, “Dermatologists should be more vigilant in prescribing antibiotics for acne patients.”8

In 2022, the Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine published an article that summarized the data about the resistance rates to erythromycin and clindamycin in various countries. Researchers found that in Jordan, over 70% of acne bacteria taken from patients were resistant to erythromycin, followed by around 60% in Japan. The lowest rate of erythromycin resistance was reported in Singapore, where it was around 30%. Similarly, when it comes to clindamycin, Jordan showed the highest resistance rate of 60%, with Japan following closely behind. The lowest clindamycin resistance rate of around 30% was observed in China.9

Interestingly, researchers have noted similar levels of resistance both in patients treated with and without antibiotics, although those who were not treated with antibiotics have somewhat lower levels of resistance.8 This is because resistant strains of bacteria are easily transmitted between people.11,12 One study even found that doctors who work with acne patients are much more likely to harbor antibiotic-resistant acne bacteria than doctors who work in other departments, suggesting that antibiotic-resistant bacteria probably get transmitted from patients to their doctors.5

Of all topical antibiotics, resistance to erythromycin is most common, as 2 scientific articles point out.3,11

Expand to read quotes from articles

According to a 2007 article in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, “Resistance has been seen with all antibiotics, but is most common with erythromycin.”3

Similarly, a 2015 article in the American Journal of Clinical Dermatology noted, “While resistance has emerged to all topical antimicrobial agents, erythromycin resistance is the most common and the drug has demonstrated waning efficacy relative to clindamycin.”11

Resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin is now a worldwide problem, which is made worse by the fact that resistant bacteria can be transferred from person to person.

Oral antibiotics are a large part of the problem because once swallowed, they eliminate many groups of bacteria, which can cause many different strains of bacteria to become resistant.11

In order to reduce the risk of antibiotic resistance, scientists recommend replacing oral antibiotics with a topical treatment regimen, such as benzoyl peroxide and topical retinoids (tretinoin, adapalene, or tazarotene), whenever possible.

If doctors do prescribe antibiotics for acne, they should combine antibiotics with benzoyl peroxide or topical retinoids, in addition to keeping treatment duration to 3 months or less. These recommendations were described in two recent article for doctors.11,13

Expand to read quotes from articles

A 2015 article in the American Journal of Clinical Dermatology states, “In an effort to reduce resistance, avoid using topical antibiotics as maintenance therapy or monotherapy. Instead, treatment should be combined with a topical retinoid and/or benzoyl peroxide and limited to the shortest possible duration. Furthermore, simultaneous use of oral and topical antibiotics should be avoided, especially if they are chemically different.”11

A 2016 article in the journal The Lancet; Infectious Diseases gave similar recommendations. The researchers combed through articles published between 1954 and 2015 to come up with guidelines for antibiotic use in acne. They wrote, “Ideally, benzoyl peroxide in combination with a topical retinoid should be used instead of a topical antibiotic to minimise the impact of resistance. Oral antibiotics still have a role in the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne, but only with a topical retinoid, benzoyl peroxide, or their combination, and ideally for no longer than 3 months.”13

Researchers also recommend raising awareness of antibiotic resistance among people with acne. A recent survey found that many younger acne patients underestimate the risks of antibiotic overuse.14

Expand to read details of survey

A 2019 article in The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology published the results of a survey that included acne patients and parents of teen acne patients. A total of 1919 participants completed the survey. The researchers found that most participants had a general understanding of antibiotic resistance, but that younger people tended to take the potential risks too lightly.14

Conclusion

As we have seen in this article, treatment with antibiotics, especially for prolonged periods of time, leads to antibiotic resistance, and this resistance is becoming a significant worldwide problem that threatens to undermine our ability to treat bacterial infections in the future. This could lead to people dying from even simple bacterial infections that we now routinely treat with antibiotics.

Given the dangers of antibiotics, they should only be used as drugs of last resort for acne treatment. If deemed necessary, they should be administered sparingly and for short duration (less than 3 months).

References

- Nagler, A. R., Milam, E. C. & Orlow, S. J. The use of oral antibiotics before isotretinoin therapy in patients with acne. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 74, 273 – 279 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26525749

- Sardana, K., Gupta, T., Garg, V. K. & Ghunawat, S. Antibiotic resistance to Propionobacterium acnes: worldwide scenario, diagnosis and management. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 13, 883 – 896 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26025191

- Strauss, J. S. et al. Guidelines of care for acne vulgaris management. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 56, 651 – 663 (2007). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17276540

- Lee, Y. H., Liu, G., Thiboutot, D. M., Leslie, D. L. & Kirby, J. S. A retrospective analysis of the duration of oral antibiotic therapy for the treatment of acne among adolescents: investigating practice gaps and potential cost-savings. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 71, 70 – 76 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24725476

- Karadag, A. S., Aslan Kayıran, M., Wu, C. Y., Chen, W. & Parish, L. C. Antibiotic resistance in acne: changes, consequences and concerns. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 35, 73-78 (2021). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32474948/

- Coates, P. et al. Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant propionibacteria on the skin of acne patients: 10-year surveillance data and snapshot distribution study. Br. J. Dermatol. 146, 840 – 848 (2002). http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/12000382

- Ochsendorf, F. [Systemic antibiotic therapy of acne vulgaris]. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 8 Suppl 1, S31 – 46 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17010172

- Luk, N. M. et al. Antibiotic-resistant Propionibacterium acnes among acne patients in a regional skin centre in Hong Kong. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 27, 31 – 36 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22103749

- Dessinioti, C. & Katsambas, A. Antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance in acne: Epidemiological trends and clinical practice considerations. Yale J. Biol. Med. 95, 429-443 (2022). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36568833/

- Del Rosso, J. Q., Leyden, J. J., Thiboutot, D. & Webster, G. F. Antibiotic use in acne vulgaris and rosacea: clinical considerations and resistance issues of significance to dermatologists. Cutis 82, 5 – 12 (2008). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18924545

- Oudenhoven, M. D., Kinney, M. A., McShane, D. B., Burkhart, C. N. & Morrell, D. S. Adverse effects of acne medications: recognition and management. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 16, 231 – 242 (2015). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25896771

- Aslan Kayiran, M., Karadag, A. S., Al-Khuzaei, S., Chen, W., Parish, L. C. Antibiotic resistance in acne: Mechanisms, complications and management. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 21, 813-819 (2020). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32889707/

- Rueda MJ. Patient Awareness of Antimicrobial Resistance and Antibiotic Use in Acne Vulgaris. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 12, 30-41 (2019). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6624010/

- Walsh T. R., Efthimiou J., Dréno B. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne: an increasing topical and oral threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 16, e23-33 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26852728

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products