Treating Acne in White Skin

The Essential Info

As with all ethnicities, acne is common in Caucasian skin, and is the top reason white people see a dermatologist.

However, Caucasian people tend to experience more severe acne lesions, but less hyperpigmentation (dark/red spots left behind after an acne lesion heals), when compared to other ethnicities.

Treatment is the same no matter what ethnicity, and there are a variety of effective treatment options.

The Science

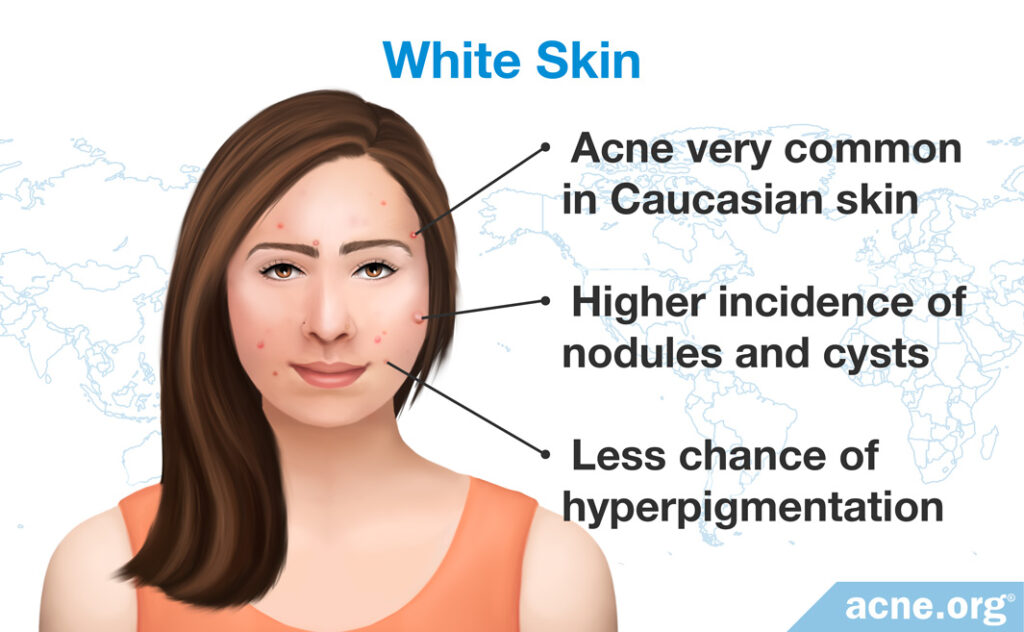

White Skin

- Acne very common in Caucasian skin

- Higher incidence of nodules and cysts

- Less chance of hyperpigmentation

- Tendency toward dryer skin

Overview

Acne is a common skin disorder in Caucasian adolescents and adults. According to Cutis, a clinical journal for dermatologists, “During visits by white patients, the…most common [diagnosis] recorded [was] acne.”1

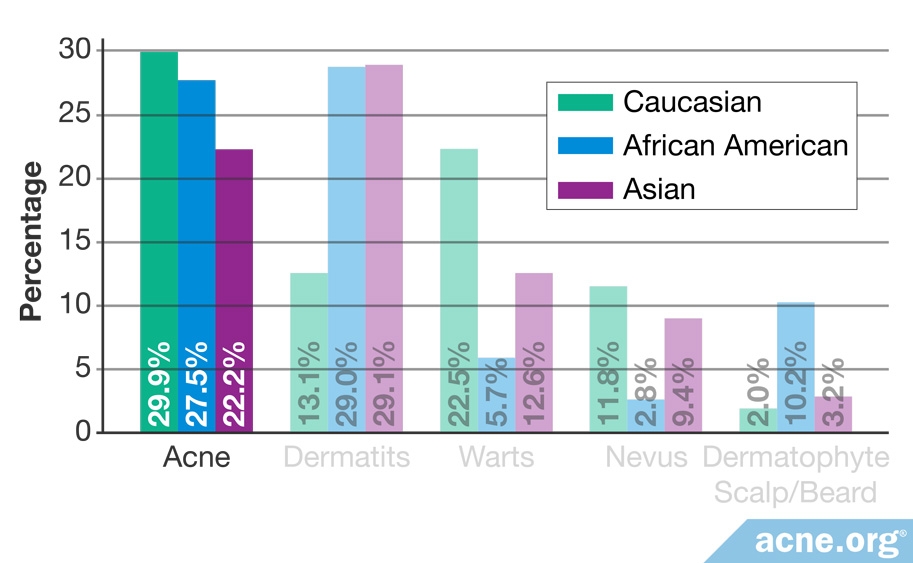

According to a recent study, white adolescents experience slightly more acne than black or Asian adolescents.2

Expand to read details of study

A study published in Pediatric Dermatology in 2012 looked at 31,153 children and adolescents and reported that acne was slightly more common in Caucasian American adolescents than in Asian or African American adolescents.2

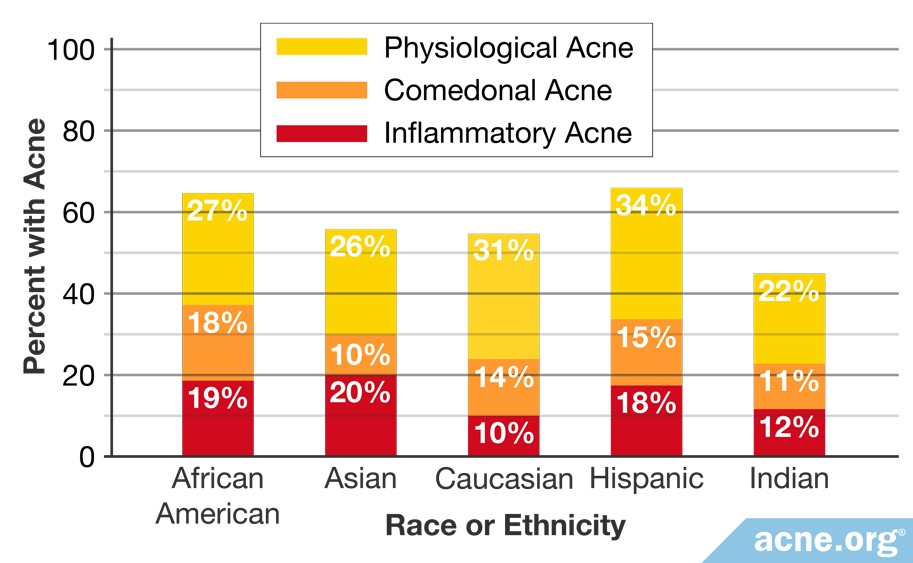

On the other hand, another recent study looked at females of all ages and concluded that white females experience less acne than any other ethnic group except Indians.3

Expand to read details of study

A study researching female participants of all ages was published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology in 2011. The researchers reported that overall incidence of acne was lower in Caucasians than any other ethnic group aside from Indians. Incidence of “physiological acne,” a term used to refer to a less severe form of acne that is sometimes present in adult women, however, was higher in Caucasian women than any other group aside from Hispanics.3

What Is Different about White Skin

People with white skin have less melanin, which gives skin it’s color. People with lighter skin also tend to have a higher incidence of nodules and cysts, the more severe types of acne lesions. Caucasian people also tend toward dryer skin, making drying and peeling medications more of a challenge. White people must also contend with more noticeable lesions when they do break out. The acute redness and inflammation that directly surround an acne lesion stand in stark contrast to light skin tones. However, when it comes to the red spots that acne leaves behind, white people tend to have less of a struggle. While white people do experience post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation – the medical term for these marks – they experience them less often than their darker-skinned counterparts.4-7 Also, these marks tend to fade more quickly on lighter skin. However, Caucasian skin, just like any other ethnicity, can scar. White skin is also thinner than darker skin types and fibroblasts, which are cells responsible for giving skin its elasticity, are less active in white compared to black skin.8

Another way that Caucasian skin differs from darker skin types is that it tends to have smaller pores. In fact, the same study that showed that Caucasians have less acne than other groups reported that there is a negative correlation between pore size and skin lightness, meaning that the lighter the skin, the smaller the pore size.3 However, more research is needed to further investigate the relationship between pore size and skin color.

How to Treat Acne in White Skin

No matter the ethnicity, acne develops and is treated the same way, and with proper medication is treatable.9 Options include proper topical treatment as well as Accutane (isotretinoin) for people with severe, scarring, and treatment-resistant acne.

In addition, since white skin is less prone to hyperpigmentation, it tends to respond well to laser treatment and chemical peels.9 Chemical peels and some lasers, particularly ablative CO2 and erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) lasers, destroy melanin and cause lightening of darker skin. Although this lightening effect usually disappears after two or three months, it can be permanent in some cases.8

The Bottom Line

Prevention is key. Preventing acne will not only improve quality of life, it will help prevent potential scarring.

References

- Alexis, A. F., Sergay, A. B. & Taylor, S. C. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis 80, 387 – 394 (2007). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18189024

- Henderson, M. D. et al. Skin-of-color epidemiology: a report of the most common skin conditions by race. Pediatr. Dermatol. 29, 584 – 589 (2012). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22639933

- Perkins, A. C., Cheng, C. E., Hillebrand, G. G., Miyamoto, K. & Kimball, A. B. Comparison of the epidemiology of acne vulgaris among Caucasian, Asian, Continental Indian and African American women. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 25, 1054 – 1060 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21108671

- Halder, R. M. & Nootheti, P. K. Ethnic skin disorders overview. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 48, S143 – 148 (2003). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12789168

- Alexis, A. F. & Lamb, A. Concomitant therapy for acne in patients with skin of color: a case-based approach. Dermatol. Nurs. 21, 33 – 36 (2009). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19283960

- Shah, S. K. & Alexis, A. F. Acne in skin of color: practical approaches to treatment. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 21, 206 – 211 (2010). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20132053

- Ho, S. G. et al. A retrospective analysis of the management of acne post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation using topical treatment, laser treatment, or combination topical and laser treatments in oriental patients. Lasers Surg. Med. 43, 1 – 7 (2011). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21254136

- Been, M. J. & Mangat, D. S. Laser and face peel procedures in non-Caucasians. Facial Plast. Surg. Clin. North Am. 22, 447 – 452 (2014). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25049128

- Czernielewski, J., Poncet, M. & Mizzi, F. Efficacy and cutaneous safety of adapalene in black patients versus white patients with acne vulgaris. Cutis 70, 243 – 248 (2002). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12403317

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products