Randomized Controlled Trials, the Most Reliable Type of Study, Present Challenges

The Essential Info

Studying the impact of diet on any disease, including acne, is difficult because to determine a cause-effect relationship a study would need to control the diet of the people studied over a long period of time, and this can be impractical and expensive.

Because of this, researchers have never performed this type of study on acne. Therefore, we are left relying mostly on surveys, which provide inconclusive evidence.

Until we have several long-term, randomized studies that control diet over a substantial period of time, determining any relationship between diet and acne will remain elusive.

The Science

- Be Careful Not to Confuse Diet-and-Acne Hypotheses with Facts

- What Are the Different Types of Studies?

- Types of Studies

- Types of Analytical Study

- Study-Design Limitations in Diet-and-Acne Studies

Investigating the relationship between diet and acne is difficult. To date, researchers have not performed randomized controlled trials to confirm that diet improves or worsens acne.

As an acne sufferer, you can experiment with a particular diet to see if your acne improves. From the research thus far, there is evidence that consuming a low-glycemic diet, including colorful fruits and vegetables and omega-3 fats, may help with acne symptoms. However, until we see repeated randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on various diets over long periods of time, we cannot know for sure how diet affects acne.

Be Careful Not to Confuse Diet-and-Acne Hypotheses with Facts

The relationship between acne and diet, in particular, is difficult to study because researchers need to consider the different types of food people eat while at the same time examining all the other variables in their lives that might also affect acne, for instance, how much sun exposure they get and their level of stress. Furthermore, acne is caused by multiple factors, including genetics, inflammation, hormones, skin cell overproduction, skin oil overproduction, and acne bacteria. Because of this complexity, combined with the fact that we have not yet seen long-term randomized controlled trials looking into diet and acne, any hypotheses regarding diet and acne are just that, hypotheses.

A quick internet search will lead you to hundreds of seemingly credible sources claiming that a particular diet works for acne, and that the “results are in,” and “diet causes acne.” Beware of such claims. While researchers have made progress, and evidence is mounting that eating a low-glycemic diet rich in colorful fruits and vegetables and omega-3 fats may in fact help with acne, we simply do not have the hard science we need to definitively conclude anything about diet and acne.

From here on out in this article, we will begin diving into the types of studies available to researchers. It will be a deep dive, and we’re about to get very scientific. So if you’re feeling interested and focused, read on! Once you understand how studies are performed, you may better understand the challenges of studying diet and acne.

What Are the Different Types of Studies?

Researchers perform studies in order to find the cause of a disease or the best treatment for a particular disease.1-4

Sometimes these studies center on how diet affects a disease, like acne.

Some types of studies are more suitable than others for answering a particular question. Before a researcher chooses a study-design, he needs to consider:

- The type of question he wants to answer. For example, “Does a certain food cause acne?”

- How many participants have acne and are available to be studied?

- How much time he does he have to complete the study?

- How much funding does he have?

Answering these questions helps the researcher determine what study-design to employ.

Types of Studies

Some studies are lower on what is called the “research heirarchy” and produce data that is less dependable, while others are higher on the hierarchy, producing data that is more reliable.

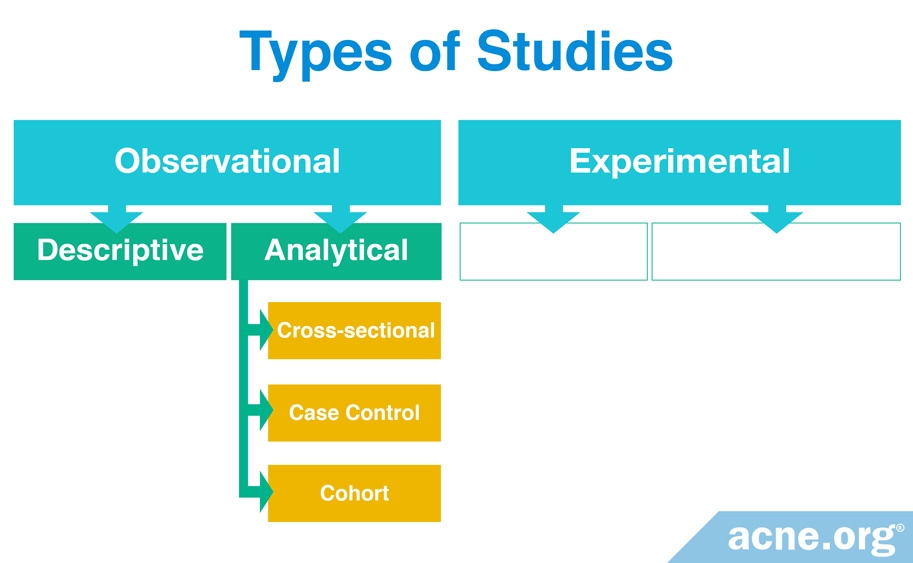

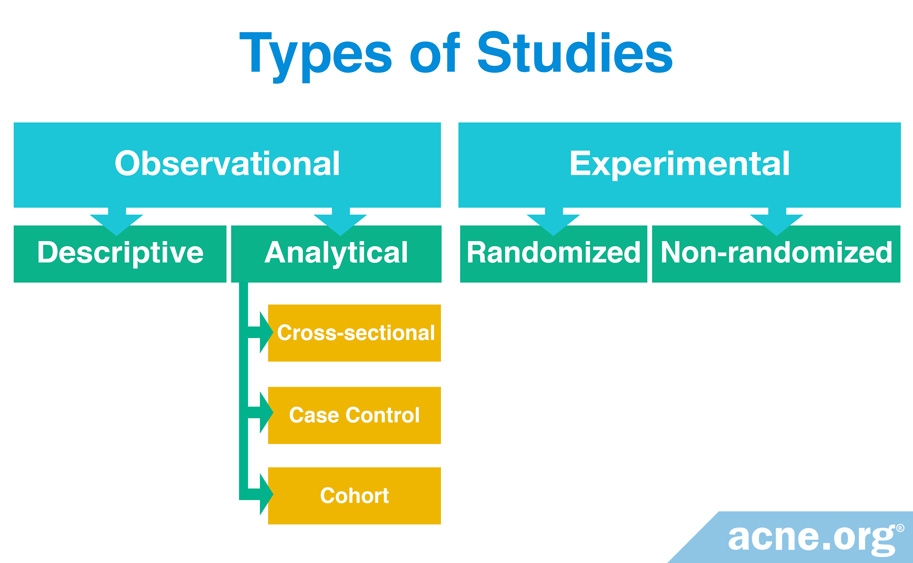

All studies can be broken down into two main categories:

- Observational (lower on the research heirarchy)

- Experimental (higher on the research heirarchy)

Observational studies are studies in which the researcher only observes what happens to the participants without subjecting participants to something called an exposure, as they do in experimental studies. An exposure is what the researchers newly-expose participants to, such as a new diet.

Observational studies are further broken down into two types:

- Descriptive

- Analytical

Descriptive studies describe certain situations, such as symptoms of acne. In this type of study, researchers look at only one group. Descriptive studies particularly on acne simply describe its symptoms, without trying to explain the cause. Descriptive studies are lowest in the research hierarchy because their purpose is only to introduce new symptoms, and sometimes new diseases, that had not been studied previously. Scientists then make hypotheses, which compel other scientists to further study the new symptoms or disease. An example of a descriptive study is a case report, which introduces a disease or symptoms of a disease that had not been seen or studied before. For instance, a case report on acne would be a description of its symptoms as seen in only one or a few people.1

Analytical studies compare symptoms of a condition between two different groups of participants, without introducing an exposure. For example, a researcher may compare symptoms of acne between a group of acne sufferers and a group of non-sufferers. The latter group would be the control group, also known as the comparison group.

Types of Analytical Study

Analytical studies represent the majority of studies performed thus far on diet and acne. There are three types of analytical studies:

- Cross-sectional

- Case-control

- Cohort

A cross-sectional study, also known as a frequency study or a prevalence study, is a kind of analytical study that observes two separate conditions at the same time. For example, a researcher may measure a participant’s sugar intake while noting whether she has acne or not.

Cross-sectional studies on acne involve two groups of participants: one group of people who have acne and another group of people who do not. If there is only one group, a researcher cannot determine a correlation between, for example, sugar and acne. However, the researcher may find a correlation if there are two groups, which allows him to see, for instance, that the group who consume more sugar experiences more acne compared with the second group who consume less sugar and do not experience acne.

In a cross-sectional study, it is impossible to answer the question, “Is there is a difference in acne between the two groups?” This is because results from a cross-sectional study do not look for a cause. They show only that a condition is more frequent in one of the groups.

A case-control study is a kind of analytical study in which the researcher begins with the outcome: for instance, in the case of acne, the researcher starts with a group of patients who already have acne and then compares it to a similar group of people (same age, gender, etc.) who do not have acne.

The researcher then questions the patients or looks at their medical charts to check whether they had been subjected to any prior exposures (e.g., a medication). If the exposure is higher in either of the groups, the researcher can conclude that the exposure is associated with an increased or decreased risk of acne.

A case-control study is useful when the outcome or disease is rare because researchers can intentionally search for participants of a specific outcome or those who have a certain disease. It also requires less time, effort, and money, compared to other types of studies.

However, a case-control study can be challenging because the researcher has to find the appropriate participants for the control group. The participants in this group must be similar to those in the other group, the only difference being that they do not have the disease.

Another challenge in performing case-control studies is that participants may not remember their past exposures when asked, so they may not be able to provide accurate answers. This leads to false information, also known as recall bias.

A cohort study is a type of analytical study that follows one or more groups of people from the time they receive an exposure to the end of the study. For example, a researcher may follow a group of teenage girls who have had severe acne for 20 years in order to see if a low-calorie diet causes a significant reduction in acne.

In the above example, the researcher would follow two groups: the first group would have severe acne, while the second group (control group) would have mild or no acne. When the study ends, the researcher can conclude whether a low-calorie diet reduces acne more in one of the two groups or not. In addition, the researcher may find a causal relationship between a high-calorie diet and a flare of acne.

There is less concern about recall bias in cohort studies than in case-control studies. Participants do not need to “recall” or remember past exposures since the researcher follows his journey closely from the time of exposure.

One major advantage of cohort studies is that they allow scientists to make accurate calculations. Some examples of calculations scientists obtain from cohort studies include:

- Incidence rates of acne – number of acne cases in a population during a number of years

- Relative risks of acne – ratio of acne probability in a population of people who consume low-calorie diets to that in a population of people who consume high-calorie diets

- Attributable risks of acne – the difference in rate of acne between a population of people who consume low-calorie diets and a population of people who consume high-calorie diets

However, cohort studies come with disadvantages:

- A cohort study requires much time. In the example above, it may not be useful to follow the participants for a short period, such as a month, as it may take years to show a consistent relationship.

- If the researcher were studying a rare disease, he would need a large group of participants (ten thousand or more) to show that there is an increased risk.

- A cohort study may become too expensive to fund because of the length of time it requires.1

Now let’s take a look at the two types of experimental studies, which unlike observational studies, includes the introduction of an exposure:

- Randomized (highest on the research heirarchy)

- Non-randomized

There are two groups in a randomized study. Researchers let chance decide which participants go into which group. The participants in one group receive a placebo (a “treatment” that does not have an effect) and those in the other group receive the study drug (e.g., an acne medication). A randomized controlled trial (RCT) is the gold standard in the research hierarchy.

Randomized studies are useful for observing small to moderate effects of an exposure. For example, if a researcher studies a new drug, one group receives it, while the other group receives a placebo. The researcher then can study any outcomes or slight effects of the exposure in the two groups.

A problem that researchers encounter in most studies is bias, which is favoring someone or something over someone else or something else. In a study, bias can lead to a false conclusion. Randomized studies help to reduce or avoid this. Examples of bias include the following:

- Selection bias, which occurs when a researcher selects the participants for the study based on her preference. Because she may not select an accurate representation of the population, the result of the study may not be reliable.

- Information bias, which occurs when a researcher knows certain things about the participants. This can result in her assuming things, potentially skewing the result of the study. The researcher is “unblinded” in this case, meaning she sees what groups the participants are assigned to. Randomized trials eliminate information bias by “blinding” both the researchers and the participants so that they do not know which participants are in the exposure group and which are in the control group.

- Bias due to confounding factors, which are factors that have a relationship with both the exposure and the disease. When confounding factors are present, the researcher may associate the result of the study with the exposure and not realize the result is in fact due to one or more confounding factors.

The following are examples of possible confounding factors when studying diet and acne:

- Sugar in diet: Some studies suggest that high glycemic (high sugar) diets affect acne. Assuming a researcher is studying the effects of a low-calorie diet on acne, it is important to keep the levels of sugar the same in both groups of participants. Otherwise, any acne fluctuation may not be the result of a low-calorie diet but rather the high sugar content. In this case, sugar is the confounding factor.

- Weight loss: Studies show that weight loss can reduce acne as someone loses weight. Let us assume that a researcher wants to study the effects of a low-calorie diet on acne and that there are two groups of participants: one group is given a low-calorie diet, and the other is given a normal diet. It is possible that the acne patients in the low-calorie diet group lose weight. In this case, weight loss is the confounding factor.

- Other confounding factors: There are other confounding factors, such as smoking, family history, and medications. Researchers should consider all factors before drawing a conclusion.

Although a randomized trial is the gold standard for diet-and-acne studies, randomized trials present some challenges, including:

- Exclusion criteria: This consists of rules that prevent a category of people from participating in a study so that the results are accurate. For example, if a researcher wants to study a new diet in association with acne, he may exclude vegetarians if the diet contains meat. Because of the exclusion, the researcher is not able to apply the results to an entire population since he did not represent every population member.

- Ethical considerations: For ethical reasons, it is not always possible to perform a randomized trial. For instance, when investigating the relationship between drugs and acne, randomly assigning participants to a particular drug without their consent would be unethical.

- Costs: As with cohort studies, randomized trials can be costly because they require much time to complete.1

In a non-randomized study, the researcher is not blinded. Rather, she is tasked with choosing who will be in the study and ultimately assigning participants to particular groups.

There also is the possibility of information bias since the researcher knows which participants are in which groups. Therefore, non-randomized studies can produce inferior results when compared to randomized studies.

However, sometimes non-randomized studies have to be performed when randomization is not possible. For instance, a randomized study would not be ethical if the exposure harmed certain people. In a diet-and-acne study, it would be unethical to perform a randomized study if the diet contained peanuts or other food items that are known to cause allergies in some individuals.

Study-Design Limitations in Diet-and-Acne Studies

So far, most studies done on diet and acne are cross-sectional studies and case-control studies. These studies have not shown that diet causes acne, but that diet may make acne worse or affect it to some degree.

The best study to provide evidence for the cause of acne would be a randomized study because it generally is free of bias. However, to date, no researcher has performed a randomized study investigating the relationship between diet and acne because of:

- Too many confounding factors: A study on diet and acne could present many confounding factors, such as different types of foods people eat and whether they are processed or organic. In addition, participants must control various influences on diet: for example, calorie or sugar intake.

- Length of time: Participants need to maintain a particular diet for the duration of the study, which could be a long time. It is difficult to ensure that participants maintain these strict diets for an extended period of time.

- Expensive/limited funding: Large randomized controlled trials are expensive because they take a long time. In addition, big food and beverage companies may not want to sponsor studies on diet and acne because they may expose ingredients in their products that worsen acne.

Study-designs come with both strengths and limitations. The best study to investigate the relationship between diet and acne would be a randomized controlled trial.3 However, due to many confounding factors, length of time, and the expensive nature of randomized studies, researchers have not performed any on diet and acne. For this reason, we are left without complete knowledge regarding the effects of diet on acne.

References

- Grimes, D. A. & Schulz, K. F. An overview of clinical research: the lay of the land. Lancet 359, 57 – 61 (2002). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11809203

- Greenland, S. & Morgenstern, H. Confounding in health research. Annu. Rev. Public Health 22, 189 – 212 (2001). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11274518

- Burris, J., Rietkerk, W. & Woolf, K. Acne: the role of medical nutrition therapy. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 113, 416 – 430 (2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23438493

- Zaenglein, A. L., et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 74, 945 – 973 (2016). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26897386

Acne.org Products

Acne.org Products